| ISSN 23958162 I www.pensamientocriticoudf.com.mx |

| ISSN 23958162 I www.pensamientocriticoudf.com.mx |

Production and merchandising of building raw materials in Cameroon: the case of Ebebda sand.

Producción y comercialización de materias primas para la construcción en Camerún: el caso de la arena Ebebda.

Joseph Nzomo Tcheunta1

Dany Rostand Dombou Tagne2

FSEG — University of Dschang, Cameroon

Abstract

This paper reports on the study of building raw materials and their merchandising, precisely on the sand from Ebebda area (Lekie Division, Cameroon). During the work on the field, we have a production of approximately 1.000 tons (T) per day in raining season, 4,400 tons (T) per day in dry season. The sale of sand allows stakeholders to take care of their family. We evaluated the shortfall due to the proliferation of clandestine quarries in Ebebda. On a day basis, it is 1,050,000 FCFA in the raining season and 3,900,000 FCFA in the dry season. Thus, we suggest to the government in the short term, to create a mining brigade. This, for staff support and merchandising of sand extracted from the depths of the Sanaga River. At the local town hall, we suggest to use the tax collected from sand transporters to improve live condition of native.

Key words: Cameroon, Sand exploitation, Sand merchandising, clandestine quarry, mining brigade.

Resumen

Este artículo presenta el estudio de materias primas para la construcción y su comercialización, precisamente la arena de Ebebda en el departamento de la Lekie, Camerún. En el trabajo en el campo, se estima una producción de aproximadamente 1.000 T por día en la temporada de lluvias, 4,400 T por día en la de sequía. Se evaluó el déficit debido a la proliferación de la clandestinidad en Ebebda por día, a 1,050,000 FCFA en la temporada de lluvias y 3,900,000 FCFA 1 en la de sequía sólo en unas veinte plantas en esa zona. Así, sugerimos al gobierno en el corto plazo la creación de una brigada minera para el apoyo del personal y la comercialización de arena extraída de las profundidades del río Sanaga. En el ayuntamiento local, sugerimos utilizar el impuesto recaudado de los transportadores de arena para el bien de la cantera y sus operadores.

Palabras Clave: Camerún, Explotación de Arena, Comercialización de Arena, Cantera Clandestina, Brigada Minera.

1 Profesor Investigador de la University of Dschang - Camerún. Contacto: jnzomo@yahoo.fr

2 Profesor Investigador de la University of Dschang - Camerún. Contacto: d.dombou@aaye.org

Introduction

In a country where the population is unceasingly increasing and where there is a higher need in housing; at the moment when Cameroon transforms itself into a vast building country; the problem of the availability of building raw material necessary for the house construction at a local level is raised. This raw material is used either for construction of housing for family’s safety, or for structuring great scale project which can boost the country economy.

During 2011, the economic performances of Cameroon were "good" and its economic growth evaluated at "more than 4%" by the Strategic Document for Growth and Employment (DSCE 2, for its acronym in French, 2009).The positive results of the Cameroonian economy are made possible due to the massive public investments, with the effective starting of the structuring great projects into the infrastructure and energy sector.Regarding the urban development, the question of housing, it arises with acuity that the problems of social housing remains as a priority and a great challenge for households, organizations and State.

Thus, in the same way, the problem arises to all those which undertake to build a house. To do this, it is necessary to be equipped with all necessary means: building raw materials and sand on the first place. After the air and water, sand is the most used resource in the world (Bernit, 1982). It represents an international turnover of USD 70 billion per year. Cameroon contribution is not insignificant, this because of the Ebebda zone which is this study’s subject. It is a zone of junction between the Sanaga River and the Mbam. It abounds remarkable sand deposits which supply to all Cameroonians needs, this with the sand coming from the other rivers (Mungo, Noun, Wouri…).

Thus, the purpose of this work is to index and analyze the operation of the various sand pits, by analysing the importance of the economic exploitation of sand in Cameroon and Ebebda in particular.

Statement of the problem

To become an emergent country by 2035, Cameroun must carry its annual economic growth rate to approximately 5.5% on average during the period 2010 to 2020. It also need to reach an investment rate of 25 % per year (by 2,020) during 25 years (Cameroon’s vision for 2,035).

However, since 2001, investment rate is approximately 18% including 2% for the public sector. This is a valid reason for increase the public and private investments substantially, leading to set up a growth strategy, considering the infrastructures development. According to the DSCE, the infrastructures provide the essential foundation where the development and the competitiveness of the economy are built. They reduce the production and transaction costs, simplify activities, increase the level of production and then induce social progress. Among all these project in Cameroon, we can quote these:

Hydroelectric project of Lom Pangar, Memve' Ele, Kribi Port Authority, Yaoundé-Douala highway construction project, 2nd Bridge on Wouri in Douala, and so others.

The housing sector is in shortage. It is estimate that more than 500,000 habitations are necessary to reabsorb the most urgent needs of the populations, in particular in the urban periphery (DSCE, 2009). The demand increases by 10% per year.

The realization of all these great infrastructures projects and habitations require as all building work, an important quantity of building raw materials: cement, gravel, laterite and sand. However, their exploitations remain complex because of the difficulties in accessing to the careers. It is also related to the costs of the equipment and especially to the disorder which reigns in this sector due to an absence of a legal control. Thus the need appears for directing our research in this field, in order to firstly raise the importance of sand and in a second time, highlight its importance in the economic development of Cameroon.

Research objectives

The main objective is to index and analyse the processing of the various sand quarries of Ebebda area. It will thus be a matter of evaluating the importance or the size of sand exploitation in Cameroun: Ebebda in particular and its economic aspect.

Specifically, is about to:

Build a cartography of the zone of study quarries ; Quantify levels of produced sand; Evaluate in terms of incomes the proportion of each participant working in the sector; Analyse the impact of the abuses (related to special charges) during the distribution of sand on its final price; Evaluate the State loss due to the proliferation of clandestine careers; Examine the possibility of a mining craftsmen control and the insertion of this activity in the formal economic circuits; Record the constraints met in this activity; Analyse the various impacts of such an exploitation on the environment.

Background of the study

About Sand.

Ntep et al. (2001) defines (according to granular materials' in geology) sand as a granular material made up of small particles coming from the disintegration of other rocks whose dimension are between 0,063 (silt) and 2 mm. An individual particle is called sand grain. Sands are identified on their “granulometry” (size of the grains). According to the system of classification used, the particle size can also lie between 4,75 mm and 5mm. Here it’s used the unified classification system of grounds (A.S.T.M: American Society and Testing Materials) as it’s used in the field of geotechnics and the civil engineering in North America. It shows the higher limits and diameter of the grains and the numbers of corresponding layers A.S.T.M, this for three range of size of grain sand: coarse sand, average sand and fine sand such sands are found in Cameroonian queries.

Mineralogical composition of sand.

The abundant minerals in the sands are already abundant minerals in the rocks (as well as less abundant), they are very resistant during transportation. Insid Inside continents, quartz is generally the first mineral in abundance in sands. The composition of sand can reveal to 180 different minerals (quartz, micas, and feldspars) as well as remains limestones from shellfish and coral (Ntep et al., 2011). We can also quote Amphiboles, Biotite, Pyroxene, Olivine, Hematite, Rutile, Apatite, Chlorite, Epidote, Tourmaline, Pyrite and “Andalousite”.

Types of sand.

There are three types of sand according to the popular terminology in Cameroon: known as "fin": it is the fine sand which comes from the depths of the marshes; another known as "Sanaga": it is the stream sand resulting from the erosion of the alluvia; and the last called "carrière": it is coarse sand resulting from crushing of basalts, granites and other blocks rock.

Notwithstanding this popular or vulgar point of view, let us note that there are three types of sand, Natural sand: It is directly extracted from the pits and is composed of silica, clay in higher proportion and dust. It is the natural version of silico-argillaceous sand. We can also mention silico-argillaceous and chemical sand.

Merchandising of mineral substances

Mineral raw materials are very unequally distributed in the world (Bernit, 1982). Those which have a high monetary value are subjected to a very active international trade. By order of importance, energetic mineral substances (oil, coal, uranium, natural gas…), invaluable and semi invaluable substances, metals and industrial minerals. Let us note that the ornamentation and building materials such as stone, clay, marble, limestone, pozzolana, sand and river gravel are also significant.

Trade of these substances is carried out in one, or in all the following systems:Authoritative fixing of the price by a group of producer which grant a monopoly. Concretely, in this case the group of plungers and the retailers have this authority to fix prices;Barter deal, such as equipment for raw materials; Private treaty price fixing between purchaser and salesman for nonstandard products or in a very competing market (the sand market in Cameroon).

Whatever the system, the mining characteristics are not the same because of their geographical situation and the layer conditions. This give great profits to most-favoured exploitations.

Presentation of hosting firm

Cameroon has a long history in mining craft industry, since 1907 with German colonization. We can note the following cases: the artisanal exploitation of Gold since 1933; the tin exploitation in the small mine within 1934 - 1968; Rutile exploited between 1935 and 1955. Until 2003, the mining activity was reduced in the hydrocarbons and invaluable substances exploitation in clandestine circuits. In 2001, a new gravitational and competitive mining code materializes the will of the government to develop its mining potential.

By N0064 decree of July 25,2003 the Prime Minister, head of the government creates near the minister of mines the CAPAM (Cadre d’Appui et de Promotion de l’Artisanat Minier), it is located in Yaoundé-Cameroon. Its objective is to install a framing mechanism which transforms local populations into contractor-producers and not into employee-consumers, this through the mineral resources valorisation.

Presentation of the studying zone

The Lekie division is located at Cameroon in the Centre region, it is named according to LEKIE River. It covers a surface of 354,864 ha, has as a chief town Monatele and have 9 districts (Batchenga, Ebebda, Elig-Mfomo, Evodoula, Lobo, Monatélé, Obala, Okola, Sa'a). The present study is related to Ebebda district, created by order in Council N92/187 of September 1,1992. Located at approximately 87 km of Yaoundé on the N4 main road and 45 km from Obala, it is extended on a surface of 300 km² for a population of 24,543 inhabitants (program ADAM/CAPAM 3 for its acronym in French). It is located between 4 20' 0" and 4 30' 0" of Northern latitude, 11 10' 0"and 11 20' 0" of longitude. It’s at 487 m of altitude. It is limited to North by river Sanaga, the South by the district of Monatele, to the West by the junction between river MBAM and Sanaga and to East by the district of SA’A.

The basin of Sanaga is almost occupied entirely by the Precambrian base covered by "formations de couverture" which have a poor extension. The great structural morphological units as well as the limits of the various petrographic formations were pointed out by Owona (1998) in the South of Yaoundé. A polyphase evolution of the facies metamorphism of granulite to the metamorphism of the green schist’s facies is noted by Mvondo (2000).We find on both side the formation of volcanic basin of Sanaga. They are concentrated much in the area of the West crossed by Noun which is thrown in Mbam. From the petrographic point of view, we meet the gneissic series of Bafia in North with an amphibolite interstratification;with the Sa'a series, where the gneissic photoliths para-derivatives and ortho-derivatives are highlighted.

The temperatures of the area of Ebebda are rather high all along the year; they vary between 23 °C and 26 °C with the maximum ones in March - April (31.1 °C) and minima in August (19.1 °C).

Relative humidity lies between 71.4 and 82 % (Eyengue, 2012).Average pluviometry varies between 1,400 and 1,500 mm of water. Precipitations are higher in October, about 317 mm and less low in December, about 4 mm.In our zone of study, we can distinguish four great periods: two wet periods, one dry period and a period of sub-drought.

These physical conditions can explain the production and the accumulation of sand on the Sanaga River. It is more precisely of physical deterioration, and chemical weathering which release from many crystals like quartz. These crystals are then moved by the water and wind. They are deposited in troughs of low pressure (valleys and rivers) where they are accumulated to form great extents of silt, sometimes covered with a thick soil also covered by the vegetation.

The quality of the habitat is one of the key indicators of the economic health for a country. The urban centres in particular, constitute a perfect illustration of this assertion. Indeed, the aptitude which is to provide to the populations the adequate living conditions oblige a city to offer the necessary means in order to satisfy household needs. The cities of the developing countries do not escape to this rule. The bad living conditions of the populations correctly show the weakness of their productivity system, this is worsened by the fast demographic growth, the not controlled urbanization and the economic situation. With an urbanization rate of 52%, Cameroon takes into account today 312 towns (results from the 3rd RGPH 4 for its acronym in French, 2005). And when it is known that the Cameroon strategic development document for 2035 focuses on the urban sector as the economic growth’s engine, this give a great challenge to the MINDUH 5 to equip these towns with infrastructures to enable them to play efficiently their role.

The main problems encountered in the field of building raw materials come from the production, the distribution and the standardization. This contributes to make the landscape architecture of our towns monotonous. These constraints are related to the weakness of industrial fabric in certain products in Cameroon and to the availability on the market of sand, gravel, cement, concrete-reinforcing steels, sheets and wood.

Materials and methods

Materials used.

The choice of these sites and the work carried out on the ground required suitable materials: A GPS receiver to note the geographical co-ordinates of the area and various quarries;A topographic map: BAFIA 1D to 1/200,000, projection WSG84 was used for the orientation; A camera for the photos; Investigations questionnaires for the collection of information was used; A microphone-receiver for the interviews; A report card and a pen.

Sampling.

The population targeted is divided into three categories (from 19 to 55 years old): owners, conveyors and workmen. Owners: we sought to know the methods of acquisition of the careers, their operations and the role which these owners and the other members of the team play; Conveyors: we sought to know the conditions under which sand is convoyed: the state of the vehicles and the roads; Workmen: (the plungers, the workers which charges the trucks), we sought to apprehend the various social inequalities generated by this activity. Because of our limited financial means, the choice of surveyed was done randomly and we set a rate of 15 % which is applied to various manpower of each quarries. The sample is composed of 63 individuals on the whole.

Quarries description.

SOCAM/Balamba: It is located at approximately 3km from Sanaga Bridge on the side of the Department of the Mbam and Inoubou. Its geographical coordinates are as follows:11013' 19 '' of longitude and 4025' 22 '' of Northern latitude. It is the stream sand which is extracted in this quarry and the activity is more significant compared to other quarries. The activity proceeds on a surface of approximately 2 Hectares; Marabot/Nlongzok: it is located at approximately 2 kilometers of the town centre of EBEBDA. Its geographical coordinates are as follows: 11019' 00 '' of longitude and 4022' 10 '' of Northern latitude. It is the fine sand which is extracted in this quarry, it extends from a surface from approximately 3 Hectares; Bridge Assi: it is located right under the bridge at less than one kilometre of the downtown area of Ebebeda. Its geographical coordinates are as follows: 11016' 20 '' of longitude and 4021' 00 '' of Northern latitude. It is the stream sand which is extracted in this quarry. Its surface is approximately one Hectare.Let us note that apart from these quarries, there are more others whose activity is clandestine because the owners do not have an exploitation permit.

Variables.

Independent variables.

The age will enable us to determine the age which is most interested in this activity;The village, the origin will help to determine the ethnos group which is devoted more to this activity and to appreciate the migratory phenomenon towards the Lekie; The sex will help us to have an idea on the allocation of the functions in the careers; The matrimonial situation will be used to evaluate the incidence of the marital status on the trade;Nationality will help to determine the number of workers from abroad.

Dependent variables.

The educational level will enable us to evaluate the education level of workers in the sector, to determine their aptitude to include/understand the phenomena and to accept the innovations for the environmental protection for example; The income and the number of people will help to determine the socio-economic impact and to include/understand the passion working on this activity;The working conditions will help to better appreciate Malayan social population;The estate of the network road, it will help to justify the difficulties of convoying sand.

Data and Survey processing.

In spite of the multitude of the sand pits which exist in Cameroon, this informal sector remains unknown. Up to now no socio-economic study, nor systematic research on sand as building material or sand for glassmaking was never undertaken. This handicap does not enable us to find existing data.Thus, the data used in this study were collected with a series of questionnaires proposed to quarries owners, conveyors and workmen.Three types of questionnaires were elaborate according to the population targeted.

In order to achieve our goals, we carried out an investigation. The above quarry was furrowed with the assistance of a "bike driver" which is at the same time a worker in one of the quarries. During this phase, the questionnaire was managed and the work consisted in having the interviews and deferring a brief reply. For work credibility reasons, three days spaced each by one week were selected for our investigations. Thus the investigation proceeded with SOCAM/Balamba quarry on august 12, 2014; with Bridge Assi quarry one week after i.e. august 19, 2014 and finally with Marabot/Nlongzok quarry on august 26,2014. This stage was preceded by a period of pre-investigation carried out one day during July 2014. It consisted in locating the various quarries and makings contact with the various owners, the mines regulator agents. It also enabled us to suit the questionnaire to the field realities. The tabulation of results was manual and also computerized, this enabled us to have the statistics and the frequency switchboards with a good precision level. The software used for this purpose is Excel (from Microsoft Office package) for the diagrams and Word for the key-boarding and the word processing.

The difficulties encountered were enormous. One of them is to have the exact information on the assets of the sector. Because it is an informal sector, the statistics were not available nowhere. It was necessary to refer to the found estimative data owners and other groups met on the place. Indeed, we was confronted to a great hostility coming from some workmen and these zone drivers. It was thus necessary to use tact and patience in order to untie tongs. Because of this hostility, the size of the target population subjected to the questionnaires and that gave answers is 50 individuals out of 63 given a percentage of 79.36%.

Table 1. Summary of manpower surveyed of the sample; source. mestrales, entre el SBC vigente y la propuesta de reforma.

|

Quarries |

Owners |

Drivers |

Workmen |

Total |

|

SOCAM/BALAMBA |

3 |

10 |

17 |

30 |

|

ASSI Bridge |

2 |

3 |

10 |

15 |

|

MARABOT/NLONGZOK |

1 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

|

Total |

6 |

14 |

30 |

50 |

Source: Own elaboration

Sand Exploitation method and materials

The exploitation of sand in Ebebda like everywhere in Cameroon remains artisanal up to now, with more than 85% (Ntep et al., 2011). The growing rate of unemployment is one of the multiplicity of the sand pits causes. West region from Mifi, Mbam to Noun, Littoral region with the Wouri River and Mungo, East region with Sangha and Sanaga in the Centre region, shown how intense the sand exploitation activity is in Cameroon.

In the majority of artisanal quarries of stream sand in Cameroon, the mining method is the same. n Sanaga quarries, the exploitation remains very difficult and dangerous. Indeed, the plungers as they are called enter the river using their dugout. They immobilize it at more than 500 meters of the bank using a long stake. After this, with a bucket, they plunge in the river water to more than ten meters sometimes to draw sand to the surface: this is the artisanal dredging (figure 1). During the intense rain season, it often happens that the waves carry away certain plungers. In the fine sand pits, the exploitation is less dangerous because it occurs in the forests. The workmen proceed initially by grubbing and cutting of the large trees, then they excavate the grounds to a depth varying between 1m50cm and 2m. Only on this moment, the extraction of sand can start. These quarries have the same configuration which is that of an open-cast mine in which the activities (Figure 1) proceed.

Figure 1. Exploitation of fine sand in Ebebda.

A plunger arising from water at BALAMBA Exploitation of fine sand in Nlongzok.

Source: Own elaboration

The material usually used in the stream sand quarries of Ebebda is made up with:Dugouts: they transport the sand from the river towards the littoral;Shovels: they are used to discharge the dugouts and to charge the trucks; and some rehabilitated and perforated buckets: these are the buckets which are dropped in the Sanaga depths, to draw sand. They use their rehabilitated side with a steel plate.

Figure 2. Exploitation Sand Material in Ebebda

Dugout transporting sand at Assi bridge. Exploitation of fine sand in Nlongzok.

Source: Own elaboration

Table 2. Summary of filing prices and incomes of workmen according to the seasons (case of the stream sand).

|

|

Dry season |

Rainy season |

||||

|

Number of filled trucks |

Per day |

Per week |

Per month |

Per day |

Per week |

Per month |

|

20 |

120 |

600 |

10 |

60 |

240 |

|

|

Filing price (Fcfa) |

500 |

500 |

||||

|

Income per worker (Fcfa a) |

Per day |

Per week |

Per month |

Per day |

Per week |

Per month |

|

10,000 |

60,000 |

300,000 |

5,000 |

30,000 |

120,000 |

|

Source: Own elaboration

a1 EURO = 655.957 FCFA, dec. 2014.

The holes on the bucket allow to easily flow the water mixed with sand during the extraction (Figure 2). Let us note that the quarry owner is the only owner of the whole material. In the fine sand pits, material is consisted of machetes, slicers, pickaxes and shovels.

Sand Truck filling in the pits: working days and prices.

At Ebebda quarries or in other ones in the Lekie, the prices are the same and they include the shares of workmen. These prices are made according to the cubage (or volume) of the truck. Find more details in the above table.

No contract binds the workmen to the conveyors. The payment is immediate and by cash;the workmen negotiate their bonus from day to day according to whether the demand is pressing or not and if the weather is nice or not.

Results and discussion

The work carried out on the ground is followed by analysis, leading to results consigned in this chapter. These results are related to the population of the sands sector, the merchandising of sand and its socio-economic and environmental impacts.

Active workers in Ebebda sand sector.

The studied population has a Cameroonian predominance. Over the 50 of interrogated people, 20 % are Malian or from Chad. These expatriates play the role of plunger in the stream sand quarries (SOCAM/Balamba and Assi Bridge). Young people are numerous than adults. Thus the person whose age is between 19 and 28 years old represent 55 % of the studied population, those from 29 to 45 years old represent 30 % and those 46 years old and more represent 15 %. The minimal age is 19 opposed to 55 years old for the maximum one; the average age is 35 years old.

Etons (44%) and Manguissas (45%) are the dominate tribes in the sector, Toupouris of North region and the others compose the rest. The domination of the sector by Etons and Manguissas is explained by the fact it is their home region. Toupouris have an intense implication in the sand pits of the Lekie.

The study also revealed that over the 50 inquired person, men proportion in the activity is 100%. The presence of the women in these careers is only for commercial purposes.

Dissimilar to the situations in the other artisanal mines, where the education level of the workmen is lower or equal to the CEP (Certificat d’Etudes Primaires), the sand pits of Lekie (Ebebda) abound more Cameroonians with an acceptable educational level. This study finds that 25% of the population have an educational level lower than CEP, 30% of workmen have CEP, 20% of then have BEPC (Brevet d’Etudes du Premier Cycle) or the CAP (Certificat d’ Aptitude Professionnelle), 15% hold of “Probatoire’’, and the rest contain those with a ‘’Baccalaureat’’ and those which made at least two academic years in an university.

Concerning the matrimonial situation, the married people dominate with 50%, then come the single with 20%, those engaged with 15%, the widowers and divorced with 15%.

Trading of Ebebda sand.

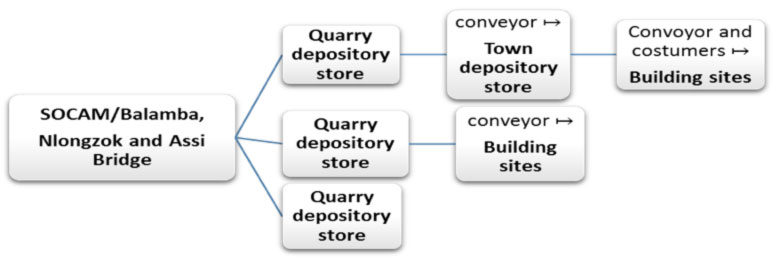

The sand trading is primarily ensured by the conveyors. They are then the strong link of the chain. So sand undergoes two types of commercial transaction in the Ebebda’s quarries before reaching final consumers. Indeed, in these pits, sand is sold to conveyors whose (most of them) work for private individual in town. The price is a function of the cubage. This sand after been purchased in quarries is sold to customers in the various town store depository in Yaoundé. The price of this final delivery is fixed by the conveyors and consist of the tipper filling price, the distance, the special levies and the accessibility of building sites. noted that the trade is directly done between the customers and the conveyors or the store depository’s owners. It can sometimes happen that customer contacts a quarry owner, them the former will find a conveyor by himself. It can be represented in the bellow figure 3.

Figure 3. Trade-circuit of sand activity.

Source: Own elaboration

Table 3. Sand prices.

|

Sand type |

Quarry sand prices (FCFA) |

Retailer sand prices (FCFA) |

||

|

Stream sand |

20 tons |

25 tons |

20 tons |

25 tons |

|

80,000 |

95,000 |

185,000 |

200,000 |

|

|

Fine sand |

25,000 |

30,000 |

130,000 |

140,000 |

Source: Own elaboration

*1 EUR = 655.957 FCFA

Prices and various factors influencing them.

The delivery sand prices are fixed by the trade union of the conveyors. These tariffs consist of several factors: the building sites accessibility, the distance, special levies, town hall taxes and cubage of the vehicle. Over these factors, distance is the most significant. It determines dearness or not of sand. The longer it is, the higher the price is. It’s important to note that tariffs are higher for the stream sand, especially when it is a matter of delivering it far from the centre region. New tariffs are influenced by the rise in the fuel prices and the Sanaga River high tide.

To transport these quantities to Yaoundé, it is necessary to spend on average 60,000 to 70,000 FCFA for the fuel purchasing, approximately 20 000 FCFA for controls, 3,000 FCFA for the city hall and 45,000 to 50,000 FCFA for the owner receipt and the “pont bascule” penalty (100,000 FCFA per extra ton during weighing).

According to the sand conveyors met on the spot, the principal purchasers are individuals, private or public companies. Most of them are retailers in Yaoundé depository stores. It is from these store depositories that the whole Cameroon sand market is supplied.

Socio-Economic impacts of sand activity.

The daily incomes of Sanaga and fine sand quarries owners are from 60,000 FCFA and 300,000 FCFA to 30,000 FCFA and 60,000 FCFA according to the seasons. These incomes are used in the major part to provide household fundamental needs, in particular feeding and accommodation. They are also used to pay the school fees of children and to a certain extent, to constitute saving in order to invest in purchasing production material for the quarry. The quarries workmen incomes (plungers and porters) hide enormous injustices. The reasons of this situation must be sought in the organization of the various groups operating in each quarry.

These workmen affirm that in spite of these modest wages they manage to suitably take care of their children and their wife.

Table 4: Daily workmen income according to seasons.

|

|

Rainy season |

Dry season |

||

|

Sanaga sand |

Fine sand |

Sanaga sand |

Fine sand |

|

|

Truck fillers; Porters Income per quarry (FCFA) |

||||

|

Average Truck filled per day |

10 |

5 |

20 |

10 |

|

Income received per truck filled |

500 |

|||

|

Daily income |

5,000 |

2,500 |

10,000 |

5,000 |

|

Plungers Income per quarry (FCFA) |

||||

|

Number of Dugout filled per day |

2 |

4 |

||

|

Income per dugout |

4,000 |

|||

|

Daily income |

8,000 |

16,000 |

||

Source: Own elaboration

Note: Plungers only work in stream sand quarries (Sanaga quarries).

Most of conveyors work for individuals whose pay to them a remuneration at the end of each month. Some rent trucks at flexible prices, between 45,000 FCFA and 50,000 FCFA per day. They can make a maximum of 3 laps per day. They can then gain an amount of approximately 5,000 FCFA per day, and consequently 150,000 FCFA per month. From the social point of view, these incomes are used to provide for the requirements in drivers’ food and their families need. They are also used to pay accommodation and the schooling fees of their children or other members of the family (brothers, sisters).

The town hall levies a sum of 3,000 FCFA 6 on the sand conveyors, those in their turn charge the expenses to the consumers. This money perceived by the town hall must be used to improve the living conditions of the bordering populations such as the rehabilitation of quarry roads, drinkable water points in the village, hangars construction for shelter, toilets in the quarries, equipment for quarries work like seals, the shovels, the life jackets, the gloves, the boots and many other. Unfortunately, nothing of all this is done up to now by the town hall, but it continues to levy its tax.

The quarries site also generated other commercial activities around it: women come to sell food to the workmen. Drink sale points do not miss there.

Evaluation of the State opportunity loss.

The proliferation of clandestine sand pits in Ebebda constitutes an opportunity loss for the State. This loss is evaluated according to the extraction tax on the quarry production (sand, pozzolanas, clay, laterites…) with an amount of 150 FCFA/m3. Let us note that we counted more than about twenty of clandestine quarries in the studied zone, including 15 of fine sand and 10 of stream sand.

Thus, State loses in dry season an amount of 93,600,000 FCFA per month and 25,200,000 FCFA in rainy season, rising an annual total opportunity loss of 712,800,000 FCFA only in about twenty clandestine quarries of Ebebda zone.

Environmental impacts of the quarries exploitation.

According to law N° 001 of April 16,2001 bearing mining code modified and supplemented by law N° 2010/011 of July 29,2010 in its Article 118, Any activity of mining and quarry must conform to the regulation in force relating to protection and management of the environment.

Table 5. State daily opportunity loss.

|

|

Rainy season |

Dry season |

||

|

Sanaga sand |

Fine sand |

Sanaga sand |

Fine sand |

|

|

Average number of truck extracted per day (20 m3 per truck) |

200 |

150 |

1,000 |

300 |

|

Quantity (m3) |

4,000 |

3,000 |

20,000 |

6,000 |

|

Extraction tax (FCFA/m3) |

150 |

|||

|

Opportunity loss by State per day (FCFA) |

600,000 |

450,000 |

3,000,000 |

900,000 |

|

Total loss (FCFA) |

1,050,000 |

3,900,000 |

||

Source: Own elaboration

But contrary to laws and decrees, the exploitation of Ebebda sand leaves many marks in the landscape. It leaves a chaotic landscape with insulated hillocks. The vegetation is sometime completely destroyed. The ground becomes more vulnerable to the phenomenon of streaming; coming from the destruction of layers. These quarries, in the majority are clandestine, they remain clandestine after their exhaustion. No process of filling after exploitation.

It results from it, great extents which are used as streaming ponding point. They constitute then in rain season places for incubation of larvae and mosquitos, constituting a threat for the native residents. Seen how desolating the place is, it is important to check if when granting authorization document to those whose have some, the proper authority poses the condition or the clause to respect condition of the environmental protection. However, we note that this condition is not especially observed, that of the fill after exploitation is allocated normally to the quarry owners. It is thus a weakness of the MINMIDT (Ministère des Mines, de l’Industrie et du Développement Technologique) and by rebound that of its decentralized authorities which do not manage to index all the operational quarries and consequently do not completely have the hand put on the exploitation in this studied zone. The main consequence is that no proceedings for infringement of environment is carried out against these quarries owners. The fill task returns in an indirect way (in long run) to the State (ministry for the mines).

Conclusion and recommendations

The activity of sand exploitation nowadays represents a significant sector for the Cameroonian economy. This study produces a document which describes and analyses the production and commercialisation process in the Ebebda main quarries. This study found that the sand trade is mostly influenced by factors like: distance, accessibility of the building sites and special levies which effect the selling price fixing. The defective condition of the road network (especially in the fine sand pits) constitutes an obstacle for this activity. Regulating the exploitation, the MINMIDT with its decentralized services and the town hall have the authority on all the quarries. However, the organization of activities and their operation depend on the quarries and store depository owners.

We noted that, because of the proliferation of clandestine quarries (approximately more than twenty in the Lekie place) the State can have an opportunity loss which is not to be neglected.The exploitation of fine sand is however not free of consequences on the environment. Many marks of after exploitation carelessness in Nlongzok place pose enormous concern to the native.

To mitigate these problems, the solution lies in a political good-will, to implement suitable and specific policies. Thus, we recommend:

At the State level, to urgently create a true mining brigade in Ebebda for the control and the commercialisation of the sand extracted in the depths from Sanaga River; We also propose to them to promote the use of modern mining instruments such as mechanical dredgers, mechanical shovels…;

Concerning the environment protection, MINEPDED (Ministère de l’Environnement, de la Protection de la Nature et du Développement Durable) and MINMIDT (Ministère des Mines, de l’Industrie et du Développement Technologique) must carry out jointly operations in order to track illegal quarry owners;

The town hall through the tax levied on sand conveyors, must install appropriate structure such as: bituminized road in the Ebebda quarries zone, construct hangars for shelter and toilets in these quarries, drinking water fountain… etc.

Notas

1FCFA : Franc de la Communauté Française d’Afrique ; Money used in Cameroon, EURO=655,957FCFA

2Document Strategique pour la Croissance et l´Emploi

3Appui au Développement des Activités Minières/ Cadre d’Appui et de Promotion de l’Artisanat Minier

4Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat;

5Ministère des Mines, de l’Industrie et du Développement Technologique.

6Approximately 150,000 FCFA (during rainy season) and 660,000 FCFA (during dry season) of tax are collected per day on the 3 quarries by the town all. 1 EURO= 655.957 FCFA.

References

Bernit, P. (1982). L’industrie minérale, Prospection et évaluation des gisements. Eléments d’économie minière.

Eyengue, A. (2012). Etude de la fertilité des aptitudes culturales des sols de Sa’a développés sur micaschistes grenatifières. Mémoire du Diplôme de Professeur de l’enseignement Secondaire 2e Grade. DI.P.E.S. II.

Mvondo, F. (2000). Contribution à l’étude Tecto-Métamorphique du secteur Mfou. mémoire de maîtrise en sciences de la terre. Université de Yaoundé I, Cameroun.

Ntep, N. P., Dupuy, J.J., Matip, O., Fogakoh, F.A. and Kalngui, E. (2011). Programme Appui au développement des activités minières. CAPAM 2011-2016.

Ntep, N. P., Dupuy, J.J., Matip, O., Fogakoh, F.A. and Kalngui, E. (2001). Ressources Minérales du Cameroun. Notice explicative de la carte thématique des Ressources Minérales du Cameroun sur un fond géologique. Notice explicative de la CTRMC/FG, MINMEE

Owona, S. (1998). Contribution à létude pétro-structurale et de la signature morphologique des métamorphites du sud de Yaoundé. Mémoire de maitrise en sciences de la terre, Faculté des Sciences. Université de Yaoundé I, Cameroun.

DSCE (2009). Document de Stratégie pour la Croissance et l’Emploi. République du Cameroun. Récupéré sur: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Project-and-Operations/Cameroon%20DSCE2009.pdf

La cooperación y su papel en el desarrollo económico y social

The cooperation and its function in the economic and social development

José Luis Bernal López 1

Tecnológico Nacional de México, Unidad Chimalhuacán

Resumen

El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar el papel que juega la cooperación en el desarrollo económico y social. Para este propósito se utilizan los principios de la economía institucional, la biología evolutiva y la teoría de juegos en una mixtura que tiene la capacidad de ampliar la comprensión de estos fenómenos sociales. Los mecanismos de la cooperación altruista son aplicables al desarrollo de las sociedades y mediante la teoría de la economía institucional y la teoría de juegos es posible modelar muchos de los comportamientos de los agentes económicos y sociales en el complejo juego de interacciones en que actúan. Se concluye que la cooperación es un elemento que ha permitido el desarrollo de las instituciones que son la base del desarrollo de las sociedades. Mientras que las actividades no coordinadas de individuos que persiguen su propio bienestar producen con frecuencia resultados que en palabras de Bowles (2010) todos tratarían de evitar.

Palabras clave: cooperación, teoría de juegos, instituciones, desarrollo.

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to analyze the role of cooperation in economic and social development. For this purpose the principles of institutional economics, evolutionary biology and game theory in a mixture that has the ability to expand the understanding of these social phenomena are used. The five mechanisms that altruistic cooperation is based are applicable to the development of societies and by the theory of institutional economics and game theory is possible to model many of the behaviors of economic and social actors in the complex game interactions in which they operate. We conclude that cooperation is an element that has allowed the development of the institutions that are the basis of development of societies. While uncoordinated activities of individuals pursuing their own welfare occur frequently results in the words of Bowles (2010) all try to avoid.

Key words: cooperation, game theory, institutions, development.

1 Profesor del Tecnológico Nacional de México, Unidad Chimalhuacán. Contacto: jolubelo1@gmail.com

Introducción

El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar el papel que juega la cooperación entre individuos en el desarrollo económico y social. Para este propósito se utilizan los principios de la economía institucional, la biología evolutiva y la teoría de juegos en una mixtura que tiene la capacidad de ampliar la comprensión de estos fenómenos sociales. Los mecanismos biológicos en los que se basa la cooperación altruista son aplicables al desarrollo de las sociedades y mediante la teoría de la economía institucional y la teoría de juegos es posible modelar muchos de los comportamientos de los agentes económicos y sociales en el complejo juego de interacciones en que se encuentran inmersos.

Los resultados observados mediante las herramientas descritas muestran que efectivamente en las sociedades en las que la cooperación es más fuerte el desarrollo económico y social es más acelerado mientras que en las sociedades donde la esta es débil el desarrollo tiende a ser limitado.

Sin embargo el resultado más relevante de la cooperación entre individuos se manifiesta sobre el tipo de instituciones que esta es capaz de generar. Es decir, se puede concluir que la cooperación es un elemento que ha permitido el desarrollo de las instituciones que son la base del desarrollo de las sociedades. Mientras que las actividades no coordinadas de individuos que persiguen su propio bienestar producen con frecuencia resultados que en palabras de Bowles (2010) todos tratarían de evitar. En cualquiera de los dos casos (cooperación o no cooperación) los efectos derivados son de larga duración (tipo de instituciones y desarrollo o falta de este) y solo se romperán en presencia de choques externos que generen nuevas formas de cooperación.

El trabajo esta compuesto por tres apartados, en el primero se aborda los mecanismos de cooperación altruista, si bien estos se derivan de la biología, tienen aplicación a las ciencias sociales y al estudio de las relaciones humanas.

En el segundo apartado se muestra mediante la teoría institucional y con un ejemplo de teoría de juegos como la cooperación incide en sobre el desarrollo económico. Mientras que en el tercer apartado se aborda el desarrollo de la sociedad usando la teoría de juegos y la institucional.

Las bases biológicas y sociales de la cooperación

La cooperación es un mecanismo necesario para la evolución, para construir nuevos niveles de organización. Genomas, células, organismos multicelulares, insectos sociales y las sociedades humanas se basan en la cooperación. Si bien la evolución implica que cada gen, célula, y cada organismo está diseñado para promover su propio éxito evolutivo a expensas de sus competidores.

A pesar de lo anterior, se ha observado que la cooperación es un mecanismo que ocurre en distintos niveles de organización biológica. Existen muchos ejemplos de cooperación entre los animales. Los humanos son sin embargo los campeones de la cooperación, desde las sociedades de cazadores-recolectores hasta la formación de los estados-nación, la cooperación es un principio decisivo en la sociedad humana. No hay otra forma de vida en la tierra que este más dedicada al mismo juego complejo de la cooperación y la deserción (Zaggl, 2014). Desde el punto de vista biológico, la cooperación significa que los reproductores egoístas renuncian a parte de su potencial reproductivo para ayudar a otros (Nowak, 2006).

Por otro lado, desde la óptica social, cooperación y democracia son sinónimos (Garrido, 2013). Adicionalmente, el mecanismo de la cooperación es una parte decisiva en el diseño de las organizaciones, entre otros beneficios, resuelve el problema de los bienes públicos y permite diseñar sistemas de incentivos, (Zaggl, 2014).

La forma más común de modelar el comportamiento cooperativo ha sido mediante la teoría de juegos, así, para Nowak (2006) se pueden identificar cinco formas de altruismo cooperativo que son los siguientes:

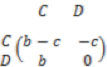

La matriz de pagos estándar entre cooperadores C y desertores D está dada como sigue:

La reciprocidad directa. Se ha observado que existe cooperación entre individuos no emparentados o entre miembros de diferentes especies. En encuentros entre dos individuos se podría asumir, si yo coopero ahora, tú cooperaras después. Por tanto, podría pagar para cooperar. El marco teórico de este juego es conocido como el dilema del prisionero (Nowak, 2006).

En los humanos la reciprocidad directa parece estar fuertemente relacionada con las emociones. En particular la emoción de la gratitud juega un papel central en la reciprocidad. Desde un punto de vista evolutivo, se puede argumentar que la gratitud y la revancha son resultados del proceso de adaptación que hacen posible la reciprocidad, (Zaggl, 2014).

En el ámbito social, la cooperación requiere estabilidad de relaciones en el tiempo y en el espacio en las interacciones entre los individuos y grupos. La democracia por ejemplo, requiere de memoria colectiva compartida, de suelo común y de expectativas de futuro comunes (Garrido, 2013). La limitante para este mecanismo radica en que requiere de repetidos encuentros entre los mismos individuos.

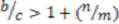

La regla de Hamilton (Nowak, 2006) establece que la selección natural puede favorecer la cooperación si el donante y el recipiente de un acto altruista están genéticamente emparentados. En forma más precisa establece que el coeficiente de relación r debe ser mayor que la proporción costo beneficio del acto altruista:

Así

La relación r se define como la probabilidad de compartir un gen. La probabilidad de que dos hermanos compartan un gen por descendencia es de 1/2; la misma probabilidad para los primos es de 1/8. La teoría de Hamilton es conocida como la selección de parentesco o aptitud inclusiva.

El mecanismo de selección espacial. Tanto en las especies animales como en la sociedades humanas las poblaciones no están completamente mezcladas. Las estructuras espaciales o las redes sociales implican que algunos individuos interactúan más frecuentemente que otros. Los modelos de estructuras espaciales en los que los jugadores solo pueden elegir dos estrategias puras (cooperar o desertar) muestran que éstos imitan las estrategias de los vecinos más exitosos (Zaggl, 2014) es decir su comportamiento se moldea mediante del efecto imitación (Akerloff & Shiller, 2009).

Las naciones, empresas, tribus, entre otras, a menudo operan dentro de ciertos territorios, por tanto interactúan más con sus vecinos que con otros. Su éxito depende entonces de imitar lo que sus vecinos están haciendo bien. De esta forma las estrategias exitosas se propagan de vecino a vecino.

Para Garrido (2013), las estrategias democráticas (cooperativas) son mucho mas empáticas y contagiosas que las estrategias oportunistas o no cooperativas. Lo anterior implica que la democracia es fuerte aun en aquellas ocasiones en que los demócratas no son mayoría.

Una regla sencilla demuestra cómo opera la reciprocidad directa, esta puede llevar a la evolución de la cooperación solo si la probabilidad w de otro encuentro entre los mismos dos individuos supera a la proporción del costo beneficio del acto altruista.

La selección por parentescos. Una propuesta adicional para explicar la cooperación es considerar la relación genética de los individuos interactuantes. La vida en forma individual sólo puede sobrevivir por un tiempo determinado y entonces la única forma de conservar los genes es copiándolos. Los parientes y en particular los descendientes son los contenedores de estos genes (Nowak, 2006). Ejemplos de la selección de parentesco en la economía pueden encontrarse en todos los casos de nepotismo (Laker & Williams, 2003), un ejemplo adicional es la fortaleza de los negocios familiares que reside en la cooperación determinada por la selección de parentesco.

Reciprocidad indirecta. Las interacciones entre humanos sin embargo, son asimétricas y fugaces. Ayudamos a los extraños que lo necesitan, donamos a la caridad que no dona para nosotros. Así la reciprocidad directa es como un canje económico basado en el intercambio inmediato de bienes. La moneda que sirve como combustible del motor de la reciprocidad indirecta es la reputación 1. Esta interacción es observada por un subconjunto de la población que puede informar a los otros. La reputación permite la evolución de la cooperación por reciprocidad indirecta. Los estudios teóricos y empíricos demuestran que las personas que ayudan más son más propensas a recibir ayuda (Nowak, 2006).

Adicionalmente, se ha encontrado que a mayor especialización, mayor diversificación en las posibilidades de consumo y menos frecuentes son las interacciones repetidas entre los mismos individuos en relación con el número total de interacciones. Así, los individuos sólo cooperarán con quien tiene reputación de haber cooperado antes, y el comportamiento oportunista es inhibido.

Las virtudes que son públicas y notorias otorgan una ventaja comparativa (reciprocidad indirecta) a aquellos individuos que la practican. Una sociedad democrática que no haga de las virtudes públicas un plusvalor social tendrá muy mermadas las prácticas y las instituciones democráticas. Pero sólo un sistema democrático puede hacer de las virtudes (del prestigio social del altruismo) un valor públicamente prestigioso (Trievers, 2008).

El resultado de una red de reciprocidad es una generalización de reciprocidad espacial. Una simple regla determina si la reciprocidad de la red puede determinar la cooperación. La proporción costo beneficio debe superar el número promedio de vecinos k por individuo.

Selección de grupo. La selección actúa no sólo sobre los individuos, sino sobre los grupos. En un modelo simple de selección grupal, una población está subdividida en grupos. Los cooperadores se ayudan unos a otros en su propio grupo. Los desertores no se ayudan. Los individuos reproducen proporcionalmente sus propios pagos. La descendencia se va añadiendo al propio grupo. Aquí debe notarse que solo los individuos se reproducen, pero la selección aparece en los dos niveles.

La selección de grupo encaja de manera cuasi perfecta en la teoría evolutiva sobre el contrato social. Esta restricción de apetitos individuales en beneficio de lo colectivo se justifica como una estrategia de fortalecimiento del grupo y de evitar la inseguridad, el conflicto o la violencia. La selección de grupos explica porque evolutivamente, la teoría del contrato social no es solo una ficción jurídica necesaria y útil sino también un relato político de algo que ocurre permanentemente en la vida social de las especies (Garrido, 2013).

Así el conjunto de valores, principios, practicas e instituciones que constituyen un sistema democrático no es sino la expresión reflexiva y social de tendencias evolutivas potentes de cooperación social de nuestra especie.

Se puede observar un resultado simple. Si n es el tamaño máximo del grupo y m es el número de grupos, entonces la selección de grupos permite la evolución de la cooperación, dada por:

Se ha encontrado que en los humanos existe una forma de moral innata (Hauser, 2009) algo así como un placer moral similar a otras formas de placer como el sexual o dietético. Esta sensibilidad neuronal hacia la conducta moral no solo es estimuladora (placer) sino también restrictiva repugnancia) ante lo que consideramos moral o injusto. Hay numerosas evidencias empíricas de la existencia del placer y de la repugnancia moral (Lieberman, 2009, citado en Garrido, 2013).

Por medio de estos dos subproductos (moral innata y placer) nuestro sistema cognitivo restringe los comportamientos egoístas y fomenta los comportamientos altruistas: la especie humana actual somos el producto de una selección multinivel que ha favorecido las conductas cooperativas sobre las oportunistas y exclusivamente competitivas.

Éxito evolutivo

Nowak (2006) muestra que el éxito evolutivo de cualquiera de los mecanismos antes descritos se puede expresar como un juego entre dos estrategias cooperadores (C), y desertores (D) dada por la siguiente matriz de pagos.

Las entradas denotan los pagos para el jugador renglón. Si no existe ningún mecanismo para la evolución de la cooperación, los desertores dominan a los cooperadores, lo cual significa que α< γ y β <δ. Pero en presencia de un mecanismo para la evolución de la cooperación puede cambiar estas inequidades, de forma que:

1) Si, α > γ, entonces la cooperación será una estrategia evolutiva estable (EEE).

2) Si, α+ β > γ + δ, entonces los cooperadores son riesgo-dominantes (RD).

3) Si α+ 2β > γ + 2δ, entonces los cooperadores tiene ventaja (CV)

En conclusión, cada una de las reglas anteriores puede ser expresada como una tasa de costo-beneficio de un acto altruista que debe ser más grande que algún valor crítico, como se resume en la figura 1.

Figura 1. Tipos de relaciones, matrices de pagos y resultado de la cooperación.

Fuente: Adaptado de Nowak (2006).

Para Nowak (2006) los dos principios fundamentales de la evolución son las mutaciones y la selección natural. Pero la evolución se construye por medio de la cooperación. Nuevos niveles de organización se desarrollan o evolucionan cuando las unidades competitivas de bajo nivel comienzan a cooperar. Quizás el aspecto más importante de la evolución es su capacidad de generar cooperación en un mundo competitivo.

Otros mecanismos de evolución de la cooperación

Siguiendo a Zaggl (2014) a los 5 mecanismos que explican la evolución de la cooperación anotados por Nowak (2006) se debe agregar los siguientes:

Selección de la barba verde. Este mecanismo es similar a la selección de parentesco, con la diferencia de que mientras en la selección de parentesco el “respaldo” está derivado de compartir parcialmente los mismos genes, en la selección de barba verde ocurre lo mismo pero sin la necesidad del parentesco.

Es decir, en este caso es necesario que la característica (la barba verde) sea reconocida por los potenciales “apoyadores” con el propósito de identificar a los portadores de este gen particular, por lo que la característica debe ser visible en el fenotipo, debe ser conspicua, algo así como una “barba verde”.

El nepotismo étnico es un ejemplo sobresaliente de este tipo de cooperación. En este contexto debe mencionarse que la selección de barba verde tiene el potencial de contribuir a la teoría de la identidad social desde un punto de vista evolutivo (Tajfel & Turner, 1986).

Reciprocidad fuerte. La reciprocidad fuerte se denota frecuentemente como “el castigo altruista”. Este término es apropiado para la forma negativa de la reciprocidad fuerte. Un individuo es un “cooperador fuerte” si gasta parte de sus propios recursos para castigar a otros que muestran un comportamiento adverso, lo es también si gasta sus propios recursos para recompensar a otros que muestran el comportamiento deseado.

En este sentido, es necesario apuntar que la reciprocidad indirecta no es capaz de sostener la cooperación en una situación de crisis. Es posible suponer que los costos de la cooperación en tales circunstancias se incrementen. Consecuentemente, las reglas generales para las condiciones de reciprocidad directa e indirecta predicen que la cooperación se desvanece en tales situaciones.

La reciprocidad fuerte en contraste con la reciprocidad directa e indirecta, tiene el potencial de sostener la cooperación aun en momentos de crisis. La reciprocidad fuerte es un mecanismo muy humano y el más importante para el diseño institucional.

Señalización costosa. La señalización costosa está enraizada en la biología evolutiva y en la economía. En los animales, particularmente los machos de algunas especies de aves, deben soportar una pesada carga por tener una apariencia sobresaliente (por ejemplo el faisán y el pavo real) que los hace más visibles para los depredadores y disminuye sus posibilidades de escapar. Los machos de estas especies demuestran sus extraordinarias aptitudes a cambio de un hándicap. Dado que las hembras no pueden verificar las aptitudes que poseen directamente, los machos toman la sobrecarga de un hándicap para mostrarlas.

En consecuencia, la calidad de la información que reciben las hembras al evaluar a sus potenciales parejas tiene un alto costo para ellos. Es importante mencionar que las señales sólo son creíbles si son costosas (Smith, 1991, citado en Zaggl, 2014). El costo está directamente conectado con la señal.

La señalización costosa también juega un importante papel en el comportamiento social de los humanos, por ejemplo en la selección sexual, objetos como los autos de lujo u otros símbolos de status son muestra de lo anterior. En las interacciones de los negocios como en la búsqueda de pareja, la información asimétrica prevalece.

Por consiguiente, invertir en la señalización frecuentemente tiene sentido para la parte que posee cualidades escondidas. Spence (1973) y Zahavi (1975) [citados en Zaggl, 2014], utilizan la teoría de la señalización costosa en la economía en el contexto de las garantías voluntarias que ofrecen algunos oferentes. Esta señalización costosa es enviada a los consumidores. El proveedor con el mejor producto tiene los menores costos para ofrecer las garantías, comparado con sus competidores. La señalización costosa es particularmente relevante cuando interactúan partes con información desigual.

La cooperación y el desarrollo económico

Las actividades no coordinadas de individuos que persiguen su propio bienestar producen con frecuencia resultados que todos tratarían de evitar (Bowles, 2010), dado que las acciones de cada persona afectan al bienestar de los demás (externalidades).

De la misma forma que en las interacciones sociales en las de tipo económico, la dificultad para sostener la cooperación que lleve a un resultado beneficioso socialmente depende de la estructura subyacente de la interacción, es decir de las creencias y preferencias de los individuos, de las relaciones causa efecto que traducen las acciones en resultados y de la interacción ocasional o continua, del numero de personas involucradas, etc.

Evitar los resultados no deseados, mientras se permite la libre elección de los individuos ha sido siempre del interés de los economistas y filósofos, a este fenómeno se le ha llamado el dilema social o el problema de coordinación. En cierta forma el capitalismo y el creciente razonamiento económico han ayudado a pasar la carga del buen gobierno de las virtudes cívicas al desafío de diseñar instituciones que trabajen tolerablemente bien ante su ausencia (Bowles, 2010).

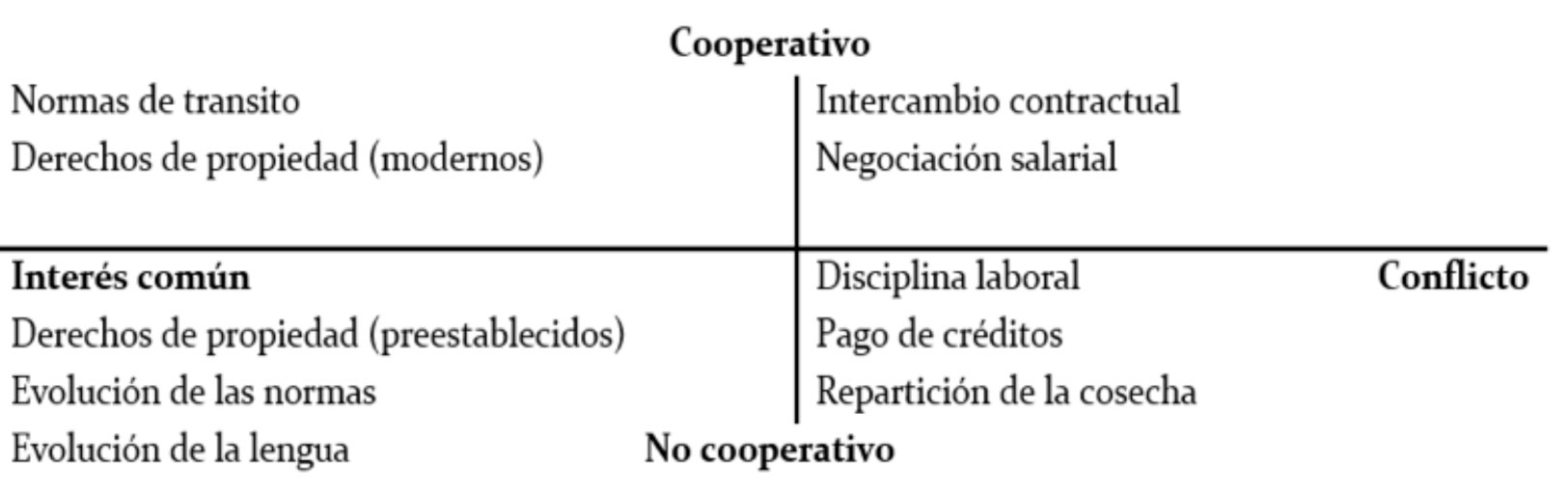

Figura 2. Formas de cooperación vs no cooperación.

Fuente: Bowles (2010).

Como puede observarse en el esquema 1, los individuos están más dispuestos a cooperar en temas que son de su mutuo interés, pero se requiere de normas que resuelvan los conflictos en los que los intereses comunes no existen o no están suficientemente claros.

Para la economía clásica la respuesta estaba en extender el interés por el bienestar a todos aquellos individuos con los que se interactúa, de forma que los efectos de nuestras acciones sobre los demás se interioricen (interiorizar las externalidades). Con el creciente alcance de los mercados, los individuos interactúan con cientos e indirectamente con millones de extraños. De aquí se desprende por ejemplo el teorema fundamental de la economía que identifica las condiciones bajo las cuales los derechos de propiedad y los mercados competitivos llevan a equilibrios Pareto eficientes, es decir que bajo las condiciones institucionales adecuadas los individuos persiguiendo sus propios intereses estarán dirigidos por la mano invisible que les llevara a resultados socialmente deseables (Bowles, 2010).

Sin embargo, es claro que cualquier proyecto común depende de las instituciones particulares que rigen las interacciones entre individuos, así los mercados, las familias, los gobiernos y las comunidades y otras instituciones relevantes son las que determinan las restricciones e incentivos, así como las normas y otros aspectos relevantes para los participantes en la interacción.

Para ilustrar el dilema entre cooperación y no cooperación se utiliza un ejemplo de teoría de juegos denominado la tragedia de los pescadores como aparece en la figura 3.

Suponiendo que dos pescadores trabajan en un lago, los peces son suficientes para que la pesca adicional siempre produzca más peces a alguno de los dos, pero cuanto más pesque uno, menos peces habrá para el otro, se supone también que 6

Figura 3. La tragedia de los pescadores: un dilema del prisionero

|

|

Pescador 2 |

|

|

Pescador 1 |

Pescar 6 horas |

Pescar 8 horas |

|

Pescar 6 horas |

1,1 |

0, 1+α |

|

Pescar 8 horas |

1+ α, 0 |

μ, μ |

Fuente: Bowles (2010).

horas es el tiempo ideal para que ninguno de los dos tenga mas pesca que el otro y por tanto se maximice el bienestar de ambos (resultado cooperativo).

En otras palabras, existe una acción para cada individuo que si se ejecuta produce mayores beneficios que cualquiera otra de las acciones disponibles. Sin embargo, si α>0, existe el incentivo para que cualquiera de los dos intente pescar más de 6 horas, suponiendo también que μ>0. Es decir el resultado cooperativo cuando ambos se limitan a pescar 6 horas es el mejor para los dos.

Por otro, lado si ambos actúan buscando su bienestar individual el resultado es peor para ambos (resultado no cooperativo). El dilema se presenta cuando se sabe que limitar la pesca a 6 horas es la mejor solución, pero siempre existe la tentación de ambas partes de pescar por un mayor tiempo a pesar de saber que ambos resultaran perjudicados.

Dicho de otra forma, dado el dilema en que se encuentran la solución para que ambos pescadores se auto-limiten esta en las instituciones, y en las amenazas de ambos de pescar más de 6 horas. Si la norma exige a ambos el límite de 6 horas y existen castigos cuando alguno de los dos la viole entonces el resultado cooperativo se impone y el bienestar de ambos es el máximo posible.

La cooperación y el desarrollo social

En forma más general, el homo sapiens evolucionó como una especie social repleto de reglas sociales, normas y comportamientos. Los humanos prosperaron precisamente por sus capacidades genéticas y sus preferencias para la cooperación que les dieron ventaja sobre sus competidores (Bowles & Gintis, 2002).

De esta forma, si ciertos tipos de instituciones políticas (formas de cooperación) aventajan o favorecen comportamientos y actitudes particulares entonces las diferencias institucionales pueden hacer que a largo plazo las consecuencias evolutivas derivadas de un simple hecho pero ciertamente estrategias políticas sean elegidas en un contexto sobre otro… estas diferencias institucionales podrían diseñar en última instancia la estructura de diferentes naturalezas humanas (Blyth et al., 2011). Si cierto tipo de individuos tienen ventaja sobre otros entonces esto puede tener efectos evolutivos sobre la forma en que se decide quién gana, quién pierde, quién se reproduce y quién no y sobre lo que preferimos, es decir las reglas de la sociedad, dado que las formas de cooperación son dinámicas, no estáticas.

Para Modelsky (2007, citado en Blyth et al., 2011), donde la selección natural actúa vía el material genético la evolución toma mucho tiempo, la selección social es más rápida e involucra transmisión cultural y actúa sobre grupos de comportamiento humanos incorporados en políticas y estrategias. Una de estas políticas es el método de “salir del paso” 2 (Lindblom, 1959, citado en Dror, 2007). Como ejemplo, en la formulación, implementación y evaluación de las políticas, los proceso de negociación, discusión, argumentación y persuasión resultan cruciales en la toma de decisiones (Majone, 1997).

Morgan y Olsen (2011, citado en Blyth et al., 2011) muestran que algunos tipos de reglas son limitantes, así como algunos comportamientos. Las reglas y las interdependencias entre éstas crean complejas redes de acciones posibles y aprobación. Solo así, el mundo es computable desde el punto de vista que para los humanos, tiene sentido, es decir qué se puede hacer en un contexto X dada la regla Y mediante los procesos sociales y el conocimiento compartido.

Las reglas (instituciones) puede ayudar a especificar tanto lo que es posible y permisible en un ambiente dado, a precisar el resultado de este dinamismo práctico cuando una regla se rompe o se dobla, se innova o se transforma, siendo las reglas mismas el aspecto visible de la intersubjetividad o la realidad.

Además dado que, las personas son heterogéneas, (algunos son más egoístas y otros tienen una mentalidad más cívica), pero también son versátiles y se adaptan en lugar de reflejar un comportamiento único para cualquier situación. Estas pequeñas diferencias en el comportamiento dan origen a instituciones cuyos resultados pueden generar grandes diferencias (Bowles, 2010).

Es decir, pequeñas diferencias en los contenidos de las reformas o incluso eventos que ocurren al azar terminan en grandes diferencias acumulativas. Algunas situaciones inducen a individuos egoístas a actuar de modo cooperativo y otras inducen a comportamientos egoístas a por parte de quienes estaban dispuestos a cooperar.

En la sociedad, las retroalimentaciones positivas 3 de las interacciones económicas y sociales crean sinergias institucionales que pueden generar ambientes en los que pequeños eventos pueden generar consecuencias duraderas y cuyas condiciones iniciales pueden dar origen a los denominados efectos encierro (lock-in) 4, los cuales solo se rompen en presencia de impactos exógenos como las guerras, el cambio climático, las huelgas, etc.

Para ilustrar lo anterior Bowles (2010) utiliza un juego de dos personas denominado, la cacería de ciervos de Rousseau, situación en la que dos cazadores deciden en forma independiente y sin conocimiento de la elección del otro, cazar ciervos (cuando se captura a uno se debe compartir equitativamente con el otro o no consumir nada) o cazar liebres (en este caso no es necesario compartir con el otro) como aparece en la siguiente matriz (los pagos son para el jugador renglón).

El juego (un dilema del prisionero) muestra como la cooperación o la falta de ella puede llevar a resultados completamente distintos, si ambos deciden cazar ciervos (cooperar con el otro) los beneficios serán mayores, sin embargo esto solo ocurrirá si existen antecedentes de que ambos cazadores han cooperado en el pasado (prestigio). En caso contrario la cacería de liebres será dominante en riesgo y ambos elegirán no cooperar.

Figura 4: Cacería de ciervos de Rousseau

|

|

Cacería de ciervos |

Cacería de liebres |

|

Cacería de ciervos |

½ ciervo |

0 |

|

Cacería de liebres |

1 liebre |

1 liebre |

Fuente: Bowles (2010)

Las implicaciones derivadas tienen mayor alcance porque establecen hacia el futuro las bases del comportamiento de los individuos, cooperar o no cooperar. Cuando los comportamientos individuales se vuelven consuetudinarios pueden transformarse en normas y estas a su vez en instituciones, luego de lo cual no existirán dudas sobre el tipo de elección de cada individuo, es decir las instituciones pueden crearse para cooperar o no cooperar.

Conclusiones

A modo de conclusión, se puede afirmar que si bien la evolución biológica tiene como una de sus bases la competencia individual, el proceso evolutivo ha desarrollado tanto en los seres humanos como en otras especies, las capacidades para la cooperación, como queda claro en el desarrollo de las sociedades humanas y sus muy complejas interacciones. Dichas interacciones requieren algún tipo de cooperación altruista: la reciprocidad directa, la reciprocidad en grupo (redes), la selección por parentesco, la selección espacial o la reciprocidad indirecta.

En el mismo sentido, los mecanismos de cooperación o no cooperación darán origen a convenciones, reglas e instituciones que al paso del tiempo moldean la forma de relacionarse de unos individuos con otros. Es decir el alcance de estas primeras elecciones no se limita al primer momento, sino que tienen efectos posteriores (retroalimentación positiva) sobre la formación de instituciones y por tanto sobre el desarrollo económico y social, así como sobre la forma de distribución de los beneficios del desarrollo, es decir el desarrollo económico y social está íntimamente ligado al tipo de instituciones propias de la sociedad y estas a su vez son la derivación del tipo de cooperación individual.

Si la elección inicial fue la cooperación el desarrollo económico y social será el resultado esperado, en caso contrario se genera el llamado efecto “lock-in” en el que se crea una espiral viciosa de pobreza y falta de cooperación, dada la complejidad de las interacciones humanas, esta trampa solo se rompe ante la presencia de choques externos. Es decir una vez iniciado el proceso de cooperación o falta de esta el proceso se auto refuerza y toma velocidad propia lo cual explica los diferentes niveles de desarrollo de las modernas sociedades humanas.

Finalmente, a pesar que las interacciones humanas son muy complejas, se han logrado importantes avances para modelarlas y entenderlas (al menos en las primeras etapas) mediante la teoría de juegos y la teoría institucional.

Notas

1 Este concepto desde el punto de vista de la antropología es lo que se conoce como el prestigio, es decir el acto altruista no tiene como finalidad obtener el beneficio de quien recibió el beneficio directo sino de la comunidad con el fin de incrementar los niveles de aceptación.

2 Implica realizar cambios incrementales con un fuerte acento en la experiencia pasada y representa una alternativa al modelo de decisiones convencional.

3 Toda situación en la cual la retribución de realizar una acción aumenta con el numero de personas que toman la misma medida (Bowles, 2010).

4 Ejemplos de lo anterior son, las trampas de la pobreza de que enfrentan algunas naciones, así como los círculos virtuosos que se producen en otras.

Referencias

Akerloff, G & Shilller. R. (2009). Animal spirits: cómo influye la psicología humana en la economía. Barcelona: Gestión 2000.

Blyth, M., Hodgson G. M., Lewis O. & Steimo, S. (2011). Introduction to Special Issue on Evolution of Institution. Journal of Institutional Economics, 7, 299-315.

Bowles, S. & Gintis, H. (2002). Homo reciprocans. Nature, 415, 125-128. Disponible en: www.nature.com

Bowles, S. (2010). Microeconomía: Comportamiento, instituciones y evolución. Edición virtual. Disponible en: https://bowlesmicroeconomia.uniandes.edu.co/

Dror, Y. (2007). Salir del paso, ¿“ciencia” o inercia? En Aguilar V. Luis (editor). La hechura de las políticas, pp. 201-226. México: Miguel Ángel Porrúa.

Fehr, E. & Gätcher, S. (1998). Reciprocity and economics: The economic implications of Homo Reciprocans. European Economic Review, 42, 854- 859.

Garrido, F. (2013). Aproximación a una fundamentación ecológica de la democracia, en Dilemata, Revista Internacional de Éticas Aplicadas, 5, (12) 63-74.

Hauser, M. D. (2009). El cerebro moral. Barcelona: Paidós.

Laker, D. R. & Williams, M. L. (2003). Nepotism Effect on Employee Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: An Empirical Study. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 3(3) 191-202.

Majone, G. (1997). Evidencia, argumentación y persuasión en la formulación de políticas. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Nowak, M. (2006). Five Rules for the Evolution of Cooperation. Science. 314, 1560-1563. disponible en: http://science.sciencemag.org/content/314/5805/1560.full

Trievers, R. L. (2008). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Reviews of Biology, 46 (1), 35-37.

Zaggl M. A. (2014). Eleven mechanisms for the evolution of cooperation. Journal of Institutional Economics, 10 (2) 197-230.

![]()

![]()